Investing is simple, but not easy. We all know that we should own great quality companies, which offer great products and services that consumer like. We also know to diversify, not trade too much, and keep investment expenses low. However, we also know that we should not overpay for quality companies as well. In addition, we know that we should not time the markets.

The fascinating part for me is that a lot of investors I speak to seem to agree with the last two statements. They know that we should not time the markets. They also know that we should not overpay for quality companies. While many investors seem to understand the theory, real world application is quite often the tough part.

The first hurdle is that waiting for a company to fall to a certain price and not investing right away is a form of market timing. This is where it is important to understand that a lot of platitudes about the stock market are just that. They are not an objective strategy to guide you through the ups and downs and the changes in the stock markets. Until you develop a strategy to invest, you would be like a blind person. Once you develop even a rudimentary strategy, and you start executing on it, you are on your way to success. This is essentially what I did between 2007 – 2008, as I was developing my screening criteria, my diversification criteria, and overall portfolio management guide.

Once you start following a strategy, the next logical step would be to keep improving on it. Continuous improvement is a management concept from Japan, which has helped a lot of companies do their best. This concept can be applied successfully to the world of investing.

I have done Dividend Growth Investing over the past 10 – 15 years, and documented my evolution on this very site here. As I kept investing, I kept noticing some recurring themes.

Notably, I would identify great companies which checked on all of the boxes. However, I would not invest either because the yield was lower than some arbitrary measure I had set, or the P/E ratio was higher than an arbitrary measure I had set. In a way, I was timing the market. Even worse, I was not investing in some good quality companies, but buying stock in companies that appeared cheap, but they turned out to be value traps. The companies I skipped on turned out to do very well, and conquer the world. I was lucky to buy into some of them when they had temporary set-backs, like when Visa was selling around 20 times forward earnings in 2015 for example. But I also missed out on others.

This is where I will insert a few quotes from Buffett, to reiterate the point I am trying to make.

"It's far better to buy a wonderful company at a fair price than a fair company at a wonderful price."

“Time is the friend of the wonderful business, the enemy of the mediocre.”

Quite often over the past 10 – 15 years I would see a company selling a little above the top of my valuation range. I would like the company, the business, its prospects, but I would sit there, waiting for a dip that never arrived.

I realized that I had set out some screening criteria which appeared to be an example of discipline and prudence. In reality, I was a little stubborn not to invest in quality companies when presented with the opportunity.

I realized that if I identify a great company, I should just invest in it. I understand that I should not overpay dearly for a great company too. However, valuing companies is more art than science. A company with a low P/E ratio that doesn’t grow earnings is more expensive than a company with a higher P/E ratio that grows earnings. You have to take into consideration the quality of the earnings stream, the possibility for future earnings growth, the possibility for disruption down the road, how long that earnings stream can last for, and how cyclical that stream is.

In general, a lot of companies are priced fairly. You can say that a company may be overvalued by a little or undervalued by a little. It doesn’t matter, because I am not in the business of forecasting short-term fluctuations in share prices. I am in the business of investing for the long-term. So as such, I benefit from along-term trends in the business, that would lift earnings, dividends and intrinsic values. Even if I overpay slightly for a quality business, over the long-run, overpayment would turn out to be a small rounding error. The far bigger problem would be NOT investing in the first place, notably because of something.

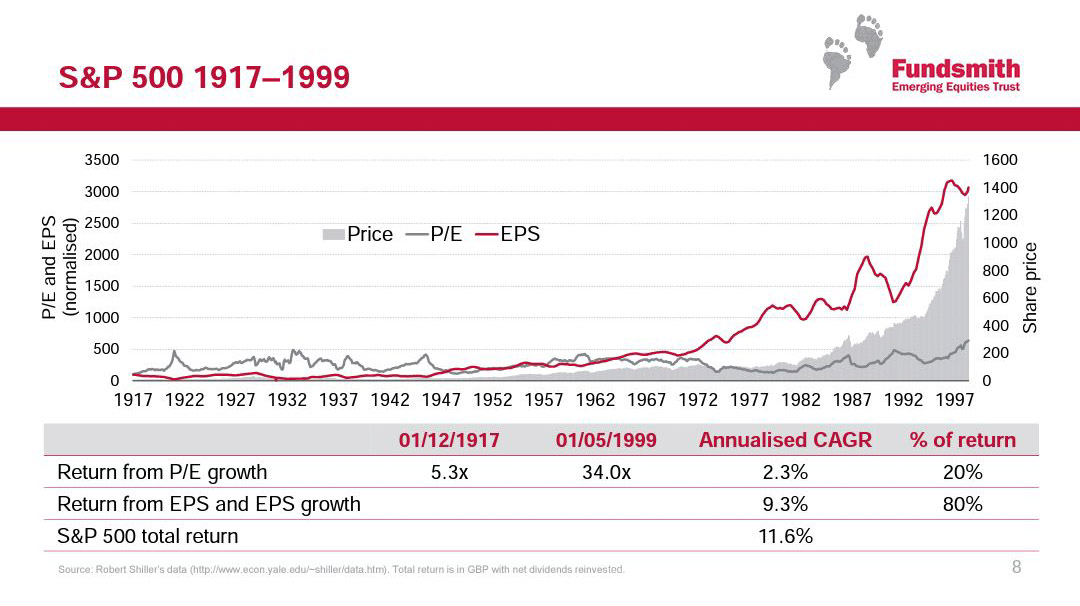

In the long run, growth in earnings contributes more than expansion of price/earnings multiples, as evidenced by this chart from Fundsmith:

(I would add reinvested dividends too however)

All of this works however, if you are going to be a patient long-term investor who will hold through thick or thin. You will not lose hope even if a position takes 5 – 10 years to start working out. You have to understand that not all positions would work, but on the aggregate, the portfolio will work wonders for the patient and persistent investor. This eliminates a large portion of the population however.

This also works great for investors who buy every month. In my opinion, the ability to invest every month is more important than the ability to buy and the bottom and sell at the top. In other words, time in the market beats timing the market. At least that's what my research found out.

The exercise that really opened my eyes was when I played some more with some historical data.

I compared a few different scenarios, in order to see if I can optimize my current situation.

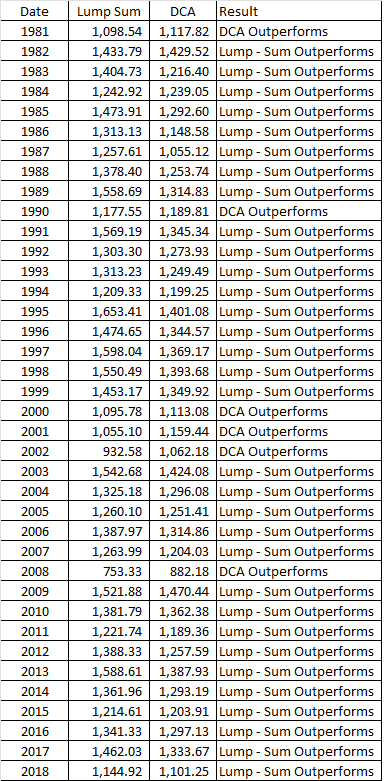

I compared investing a lump sum at the beginning of the year with spreading it over the next 12 months. It turned out that lump-sum investing did better than spreading it over. Check this article on dollar cost averaging versus lump sum investing:

This is successful, because the US market historically goes up. That’s because earnings go up, companies pay dividends that go up and they get reinvested. Earnings that are not distributed are reinvested as well, which further grows business earnings power ( on aggregate). If you look at historical data, US markets are up in 70% of the years. That’s a very strong long-term tailwind. Yes, there will be days, months, years and perhaps even a decade where stocks go nowhere. Example was the 1930s, 1970s and 2000s. But the probability of a higher decade is much higher than for a lower decade. On a random day, there is just a 50% probability that stocks would go up or down. But on an annual or decade basis, it is 70% to 80%.

As you can see, the stock market as a whole tends to exhibit an upward bias over time. It is not all the time of course, and there are always obstacle along the way. There are always clouds on the horizon, and changes. There are always "reasons" to sell or not to invest. Yet, it has built a lot of wealth over the past decades for patient, long-term investors.

Source: BlackrockI did this on purpose, because a lot of readers have kept asking me if they should wait for a market crash or a decline, before they put money to work.

I also tested whether it makes sense to buy at the top each month, at the bottom each month or jut at the closing price for an index fund. This is a proxy for a stock portfolio. Turns out that being always wrong each month or always right each month is just overrated. The goal is to select good quality companies, and buy them each month whenever you have money to invest. Instead of waiting for a dip, buy when you have money to invest.

This approach works best for someone like me, who is investing every month, and is buying several companies for their portfolio on a regular basis.

For the past several years, whenever I have had money to invest, and quality companies to invest in, I would just invest in it.

What is the point of this article?

Investing is difficult. We do not know exactly how the future would turn out. Nobody really knows for sure if a stock is cheap today or expensive. This is why our valuation techniques should be questioned constantly, because they are prone to error. A company with a low P/E may turn out to be more expensive than a company with a high P/E, if the latter grows earnings and the former doesn’t. It’s a balancing act, where we do not want to chase yield or chase growth and overpay for it. Valuation is part art, part science, which is why formulaic investing can fail you, if you do not have enough fail safe mechanisms in place. Selecting quality companies is a good start, as is diversifying across companies, industries, and time. Continuously reviewing investments, and your process, can help identify improvement opportunities.

In my case, I still start my review by looking at growth in earnings per share, dividends per share, dividend payout ratio, buyback history. I also look at trends in P/E ratios over the past decade, in addition to P/E ratios along with dividend growth to make a quick estimate of company quality, profitability and possibility for this future growth to continue. I have realized that having a minimum yield is counter-productive, so I have eliminated that from my process. I have also realized that having a P/E of 20 is overly limiting as well, so I have removed that from my process as well. That doesn’t mean I will be willingly paying 40 times earnings for a company. But I would consider paying up to 30 times forward earnings for a quality company that can grow earnings over the future. Investing is all about finding the right balance in my opinion, and not being too rigid. But not being too complacent either.

In my case, it is also easy to just invest in a lot of companies every month, through the ups and downs. This is a smoothing mechanism, that takes care of things for me. I have also increasingly started DRIPing my dividends, rather than pool them and allocate them manually.

The goal of this exercise is to overcome my fears, and invest decisively, without paralysis by analysis.

So next time I identify a quality company with good prospects that’s not excessively expensive, I will think of the following right before I click the “buy” button:

“Just do it”